Australia’s 2024-25 Federal Budget: Deficit, Data & Distributional Dynamics

The 2024-25 Commonwealth Budget marks a decisive policy pivot after two consecutive surpluses, projecting an underlying cash deficit of A$27.6 billion (-1.0 per cent of GDP) and signalling the Albanese Government’s intention to put cost-of-living relief ahead of short-term fiscal consolidation. This essay reviews the macro-fiscal backdrop, the major revenue and expenditure measures, and the medium-term sustainability issues that arise.

Macroeconomic and Fiscal Context

Treasury’s macro-assumptions present a classic “soft-landing” narrative. Real GDP growth is expected to lift from 1½ per cent in 2024-25 to 2¼ per cent in 2025-26, while headline inflation, already back inside the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) 2-3 per cent target band, is forecast at 2½ per cent across 2024-25 before nudging to 3 per cent in 2025-26. The unemployment rate is assumed to peak at 4¼ per cent in mid-2025 and then stabilise.

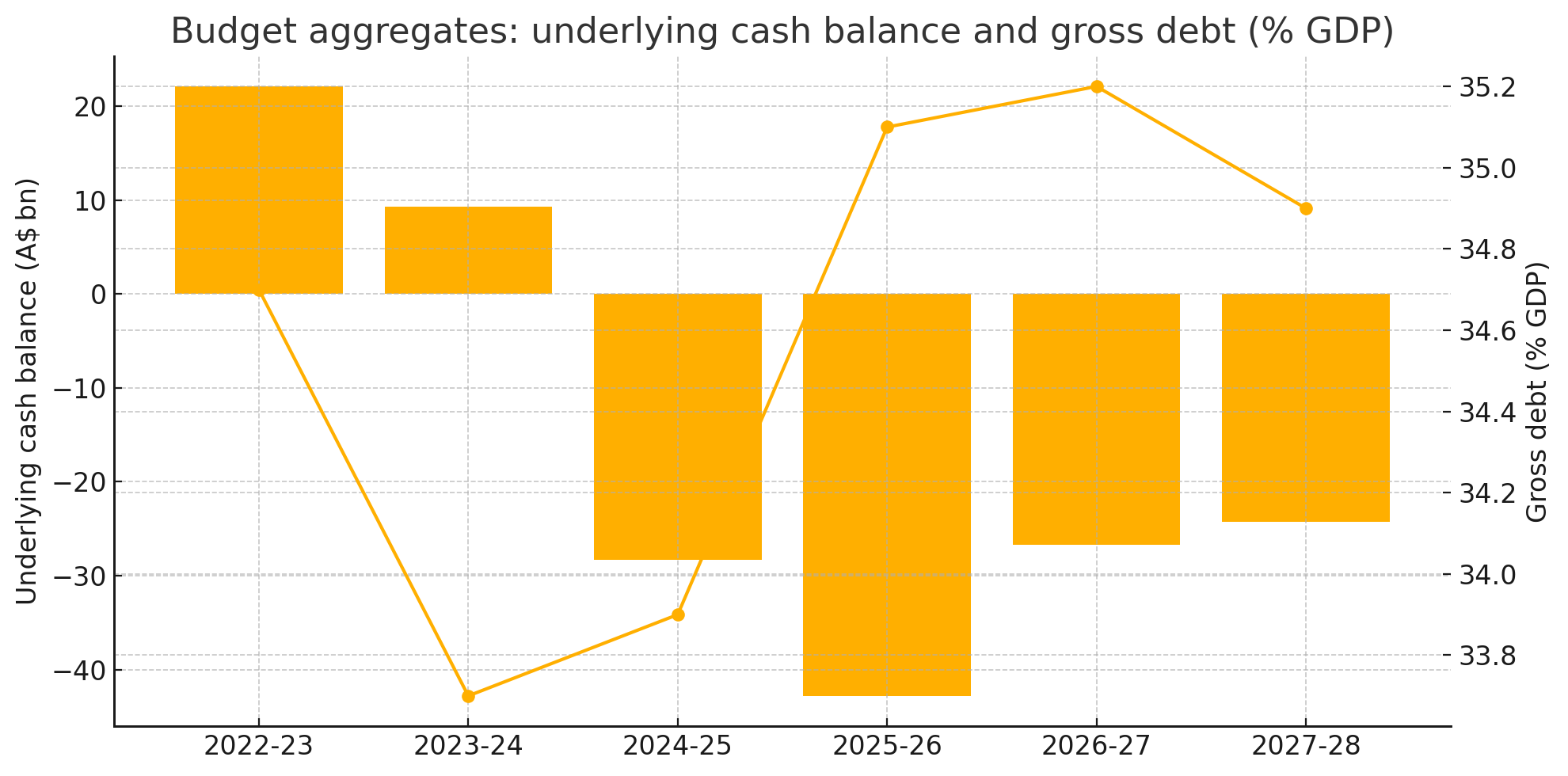

These benign forecasts allow the Government to argue that a modest deficit will not stoke inflationary pressures, especially as the structural budget position (the balance adjusted for the cycle and temporary commodity-price windfalls) is estimated to be broadly unchanged from 2023-24. But gross debt resumes an upward trajectory, rising from A$906.9 billion in 2023-24 to A$1.02 trillion in 2025-26—35.5 per cent of GDP—even after the stronger-than-expected tax take of recent years. Interest costs therefore remain a latent vulnerability once global rates normalise.

Revenue Measures: Re-sequencing the Stage-Three Tax Cuts

Headline relief comes via a two-stage “top-up” to the redesigned stage-three personal income-tax cuts. From 1 July 2026 the 16 per cent rate on incomes between A$18 201 and A$45 000 falls to 15 per cent; a year later it drops to 14 per cent, costing A$17.1 billion over five years. A worker on the average wage (≈A$79 000) ultimately gains A$2 190 per annum from 2027-28, or about A$42 a week. Low- and middle-income earners benefit most in proportional terms, but a flatter schedule still delivers absolute dollar gains that rise with income, raising perennial equity questions.

Beyond income tax, the budget continues the crackdown on multinationals and the “shadow economy”, funding the Australian Taxation Office with an extra A$1 billion over five years to net an estimated A$3.2 billion in additional receipts. These compliance dividends help offset the revenue cost of the tax cuts without raising headline rates.

Expenditure Priorities: Cost-of-Living and Human Capital Investment

Energy Rebates

Every household—and around one million small businesses—receives two further A$75 credits on quarterly electricity bills, extending the scheme to December 2025 at a fiscal cost of A$1.8 billion. Although Treasury argues the initiative is “non-inflationary” because it subtracts from headline CPI, it nevertheless delays the price signal that would otherwise foster energy efficiency.

Health and Aged Care

An additional A$7.9 billion is committed to bulk-billing incentives so that “nine out of ten GP visits are free by 2030”, alongside A$1.8 billion for public-hospital elective surgery and 50 new Medicare Urgent Care Clinics. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) co-payment falls further to A$25 per script, costing A$784.6 million.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme remains the fastest-growing program; expenditure rises from A$49 billion in 2024-25 to a projected A$63 billion in 2028-29, testing the credibility of the Government’s longer-term savings agenda.

Housing and Education

Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) commitments continue, supplemented by A$2 billion to accelerate social-housing starts and up to A$10 000 for apprentices in construction trades—moves aimed at both supply and workforce bottlenecks. On education, the budget earmarks A$5 billion for an embryonic universal early-childhood-education system, permanent Free TAFE, and increases to Commonwealth rent assistance for students.

While these allocations align with productivity-enhancing human-capital theory, their rollout speed relative to labour-market tightness will determine real-world impact.

Distributional Impact and Inflation Interface

Private-sector modelling suggests combined pocket-book measures (tax cuts, rebates, cheaper medicines) deliver average household relief of more than A$15 000 over four years. For the bottom quintile, the energy rebate is proportionally more valuable than the tax cut; for high-income households the reverse is true. The RBA’s Assessment of Monetary Policy, released the week after budget night, maintained a “mildly restrictive” stance but acknowledged the fiscal package would trim headline CPI by roughly 0.25 percentage points in 2025 before adding similar pressure in 2026 as rebates lapse—a credible trade-off given real-wage gains remain nascent.

Medium-Term Pressures: Debt, Demographics and Delivery Risk

Despite a cumulative A$207 billion improvement relative to the 2022 Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Outlook, the underlying cash balance swings back to deficits averaging 1.2 per cent of GDP beyond 2025-26, and gross debt peaks near 37 per cent of GDP late this decade. Ageing, defence modernisation and the clean-energy transition add structural outlays estimated at 2-3 per cent of GDP. Without further revenue-raising or program redesign, the current savings ratio of 69 per cent of upward tax-receipt revisions will need to be sustained well into the 2030s.

The Government points to restrained real payments growth (1.7 per cent annual average to 2028-29) and its A$94.1 billion in “responsible savings” as evidence of discipline. Yet those savings rely heavily on temporary commodity terms-of-trade assumptions and non-recurring reprioritisations; they could unwind quickly if iron-ore spot prices fall faster than Treasury’s glide-path to US$60 per tonne.

Policy Assessment

From a Keynesian standpoint the budget’s mildly expansionary stance is defensible: private consumption has been suppressed by high mortgage servicing and real disposable-income stagnation; a targeted fiscal impulse can cushion demand without overheating labour markets. Critics, including CPA Australia, counter that the package under-delivers for productivity-constrained small firms and risks entrenching a culture of “fiscal firefighting” rather than structural reform.

Moreover, the sequencing of personal-tax relief raises political economy concerns. By back-loading the second-round cuts to the 2027-28 year, the Government minimises immediate revenue loss but creates a future funding cliff that coincides with the point at which ageing and health costs accelerate. Without an offset—such as broad-based consumption-tax reform or bracket-creep recapture—future treasurers may face steeper consolidation tasks.

The health-sector injections rightly address access and equity gaps, yet success hinges on workforce supply. Expanding bulk-billing while capping provider fees risks GP shortages in regional areas unless accompanied by long-lag training pipelines or immigration streams.

Finally, the energy-relief programme, though politically popular, illustrates the tension between short-run assistance and long-run price signals needed for decarbonisation. A better-targeted mechanism (for example, means-tested vouchers) might have preserved behavioural incentives while still damping inflation.

Conclusion

Australia’s 2024-25 Budget is best viewed as a calibrated bet: that inflation is sufficiently tamed to allow a shift toward household relief without reigniting a wage-price spiral, and that modest projected deficits can coexist with declining debt-to-GDP ratios once growth rebounds. The numbers broadly support that bet, but only so long as global shocks remain muted and commodity prices stay supportive. The real test will come in mid-decade, when back-ended tax cuts, demographic spending and climate-transition costs converge.

For now, the budget succeeds in easing pressure on low- and middle-income households, reinforcing Medicare, and nudging investment in housing and skills. Whether it also lays the groundwork for medium-term fiscal sustainability will depend on the Government’s ability to transform one-off savings into durable structural reform—and on its willingness to re-open the revenue debate that every forward-estimate table says is coming.